Built-to-Rent Construction Cost per Unit: Townhome vs Detached vs Horizontal Apartments (2026)

1) Why “cost per unit” comparisons mislead (and what to compare instead)

If you’re underwriting BTR in 2026, the fastest way to get a false “best product type” answer is to compare cost per door without asking what’s driving it and how long that door takes to deliver.

Two projects can show the same “$X per unit” and behave completely differently in the model:

- One has short utility runs, repeatable foundations, simple rooflines, and a framing scope that moves predictably.

- The other has long site utility runs, frequent plan exceptions, envelope complexity, inspection churn, and a schedule that stretches carrying costs and delays absorption.

For operators and programmatic GCs, the decision is rarely “what’s cheapest to build.” It’s:

- What pencils best at stabilized NOI given density and rents

- What de-risks delivery across phases (labor, inspections, RFIs, rework)

- What compresses cycle time so your capital works sooner

This article frames the comparison the way your pro forma experiences it: hard costs + site/utility intensity + schedule profile + repeatability.

2) Definitions (the three product types as operators actually build them)

Townhome BTR (attached for-rent)

Attached side-by-side units (often 2–3 stories) designed to feel SFR-like while capturing shared-wall efficiency. Key characteristics: party walls, repeating pods, and roofline discipline (or lack of it).

Detached SFR BTR (single-family rental communities)

Stand-alone homes (often 1–2 stories in many markets). Key characteristics: more exterior perimeter per door, more site/utility length per door, and a tendency for plan drift unless options are tightly controlled.

Horizontal apartments (garden-style flats / walk-ups)

Typically 1–3 story buildings with stacked flats, breezeways/corridors, and shared infrastructure. Key characteristics: high density, fewer laterals per door, and more life-safety/acoustic/coordination requirements.

3) Quick comparison (Table A): drivers + risks + schedule profile

4) What’s inside “cost per unit” (the cost buckets to sanity-check your pro forma)

When operators say “cost per door,” they’re usually bundling multiple cost systems that don’t behave the same way across product types. Use these buckets to isolate what’s actually moving:

A) Framing + structural

- Stick framing vs engineered systems changes labor exposure more than material exposure.

- Complex rooflines, offsets, and non-repeating details are where “framing” silently expands into schedule risk.

B) Foundations

- Detached product is where foundation variance shows up (lot-specific changes, slopes, soils, on-site decisions).

- Townhomes and horizontal apartments tend to benefit from repeatable foundations when the site plan is disciplined.

C) MEP rough-in (and the “productivity tax”)

- In horizontal apartments, stacking and distribution can be efficient if coordinated early.

- In detached product, MEP is replicated many times across dispersed addresses, raising inspection and remobilization friction.

D) Exterior + envelope

- Perimeter per door matters. Detached has the most exterior per unit.

- Townhomes reduce exposed wall area via shared walls, but roofline complexity can erase the advantage.

E) Interiors + turns

- Not just build cost: unit mix drives lifecycle operating friction (turn costs, maintenance access, standard parts).

- Programmatic finishes matter because substitution chaos equals schedule chaos.

F) Sitework, utilities, and offsites

This is the “quiet giant” in per-door comparisons:

- utility laterals

- detention, grading, paving

- transformer/power availability

- water/sewer taps and fees

- offsite road improvements

G) Permitting/impact fees (market-dependent)

Not a construction line item, but it behaves like one in the pro forma. Some jurisdictions penalize doors; others penalize trips/impervious coverage; others penalize square footage.

H) GC fee, general conditions, and contingency

General conditions are where time becomes money. If one product type adds 60–120 days to delivery (even if hard costs are similar), it can lose on IRR.

Important: General conditions and contingency tend to expand in the same direction as schedule variance. If a product type increases cycle-time volatility, it usually increases GC exposure even if the “hard cost per SF” looks fine.

5) Real drivers by product type (the most practical way to evaluate “what pencils”)

Driver 1: Density and land + utility runs (the per-door reality)

Detached SFR BTR often looks attractive at a per-SF build number, but it can get punished on:

- linear feet of utilities per door

- paving/curb/sidewalk per door

- distributed inspections and remobilization

Horizontal apartments typically win on utilities per door because infrastructure is concentrated. Townhomes sit in the middle: higher density than detached, but still lots of individual unit drops.

Operator takeaway: If land is scarce or offsites are heavy, density can beat “cheaper per SF” every time.

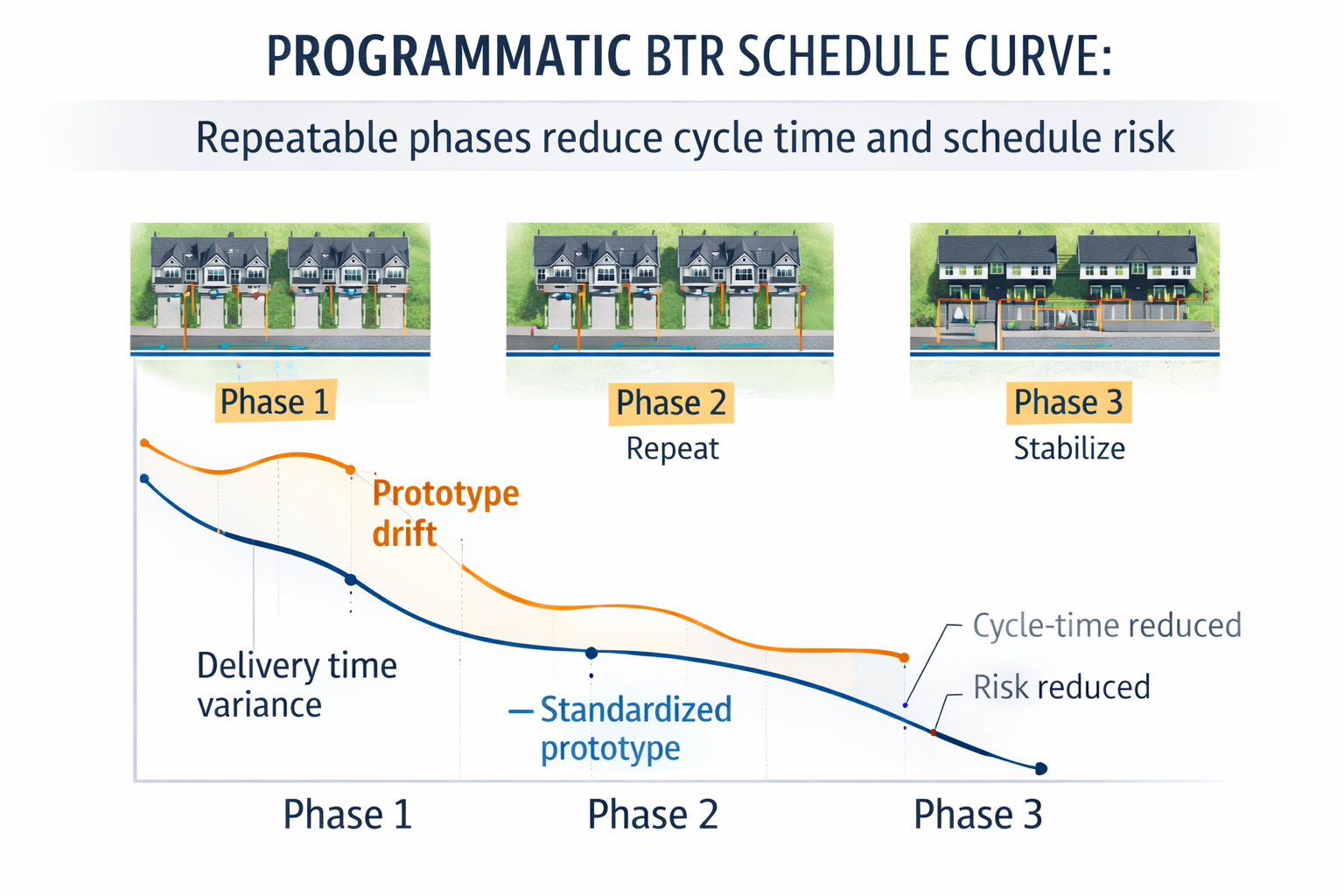

Driver 2: Repetition and plan standardization (the compounding effect across phases)

Programmatic BTR is not one project. It’s a prototype deployed multiple times.

- Detached product often drifts into “semi-custom” quickly: elevation variants, garage options, porch changes, window shifts.

- Townhomes can be extremely repeatable if you enforce a tight plan set and control options.

- Horizontal apartments are naturally repeatable by building, but only if details (fire, acoustics, MEP chases) are locked early.

Operator takeaway: Standardization is the only lever that improves cost, schedule, inspections, and maintenance at the same time.

Driver 3: Envelope complexity and rooflines (where “attached” can lose)

Townhomes should benefit from shared walls, but they often get value-engineered into complicated roof transitions, jogs, and offsets to “differentiate” units. That can:

- slow framing

- increase flashing risk

- create more inspection comments

- increase warranty exposure

Detached homes also suffer from roof complexity because each unit pays for its own roof perimeter and valleys.

Horizontal apartments can be envelope-efficient (simple gables, repeated trusses) or surprisingly complex (multiple stair towers, breezeways, articulation).

Operator takeaway: If you want predictable delivery, enforce “simple roof, repeated details.” Differentiation belongs in finish packages and site amenities, not roof geometry.

Driver 4: Foundations (slab vs stem wall vs pier variations)

Detached communities often absorb cost creep through:

- lot slopes and drainage decisions

- stem wall transitions

- field changes when forms don’t match the plan

- inconsistent anchor/holdown placement (and the inspection churn that follows)

Townhomes and horizontal apartments can be foundation-efficient because repetition shows up faster—as long as the civil and building grids are coordinated up front.

Operator takeaway: The cheapest foundation is the one you can repeat without field debate.

Driver 5: Fire separation and acoustic assemblies (where relevant)

Horizontal apartments and attached townhomes can incur higher assembly requirements depending on jurisdiction and design:

- rated separations

- draftstopping

- sound attenuation assemblies

These aren’t just material costs. They’re execution costs: the same assembly done three different ways by three different crews is where inspections and rework multiply.

Operator takeaway: If you’re building attached product, the “assembly playbook” must be consistent and pre-coordinated.

Driver 6: Labor availability and productivity variability (the 2026 constraint)

Labor is not just a unit cost—it’s a volatility source. Two communities with the same budget can diverge because:

- framers rotate crews

- productivity swings by superintendent

- rework grows with field layout drift

- trade stacking becomes chaotic

Detached product is exposed because it’s dispersed and repetitive across many addresses. Horizontal apartments are exposed because coordination is heavier. Townhomes are exposed when rooflines and transitions get complex.

Operator takeaway: The product type that wins is often the one that stabilizes labor scope and reduces “field decision volume.”

Driver 7: Inspection cycles and rework probability

Inspection risk is a schedule risk disguised as a quality issue. Repeatable prototypes reduce:

- inspection comments

- resubmittals

- “that’s not how we did it last time” variability

Detached communities have more inspection events across more addresses. Horizontal apartments have fewer addresses but more complexity per inspection. Townhomes sit in between.

Operator takeaway: A repeatable inspection path is an IRR lever.

6) Schedule + IRR lens: cycle time is a cost category (even if it’s not in your hard costs)

If you’re deciding between townhome, detached, and horizontal apartments, you’re not only buying construction. You’re buying a delivery curve:

- How quickly can Phase 1 start leasing?

- How reliably can Phase 2 and Phase 3 repeat the same cycle time?

- How much capital sits idle while you wait on framing, MEP rough, or inspections?

In operator terms:

- Shorter cycle time reduces carry and pulls forward revenue.

- Predictable cycle time reduces contingency burn and protects absorption assumptions.

- Repeatable phase execution makes your “engineer once, deploy everywhere” model real—your team gets faster, RFIs drop, and subs stop relearning the project.

A practical way to compare product types:

Instead of asking “what’s the cheapest per door,” ask:

“Which product type gives me the most doors delivered per month after the learning curve?”

- Detached often delivers early doors quickly but can lose predictability across dozens/hundreds of dispersed starts.

- Horizontal apartments can deliver large batches per building but may have longer critical path items.

- Townhomes can be the “sweet spot” when standardized: repeatable pods, higher density than detached, simpler coordination than apartments (if the architecture stays disciplined).

7) What changes the math the most (the levers that actually move cost per unit)

If you’re looking for “value engineering,” focus on levers that reduce cost and reduce risk. The best levers improve: productivity, inspection outcomes, procurement stability, and schedule predictability at the same time.

Below are the levers that most consistently move cost per unit without sacrificing quality.

8) Two mini examples showing why standardization changes outcomes

Mini example 1: detached SFR prototype drift vs locked prototype

Scenario: 180-door detached BTR, three phases of 60.

- Version A: 6 elevations + multiple garage options + frequent window shifts

- Version B: 2 elevations + single garage condition + locked openings

Typical outcome pattern

- Version A accumulates plan exceptions, RFIs, and inconsistent inspection outcomes. Phase 2 and Phase 3 do not get faster—cycle-time variance remains high.

- Version B captures the learning curve. Trade partners plan labor more accurately. Inspection outcomes become repeatable. The project behaves more like a program than a series of one-offs.

Operator takeaway: Detached can work—if you enforce manufacturing-style option control.

Mini example 2: townhome pods with repeatable framing scope

Scenario: 220-door townhome BTR with repeated 8–12 unit buildings.

- Version A: three roof conditions + frequent end-cap changes

- Version B: one primary roof geometry + repeated details + consistent openings

Typical outcome pattern

- Version B reduces framing-cycle variance building-to-building and tightens dry-in, which stabilizes downstream trades. Schedule predictability becomes a pro forma lever—not a hope.

Operator takeaway: Townhomes win when you protect repetition from architectural drift.

9) Bridge: “Engineer once, deploy everywhere” (where panelized framing fits)

Programmatic BTR works when you reduce field variability and move decisions upstream.

That’s the logic behind panelized cold-formed steel framing as a delivery method: resolve structure and coordination early, then deploy a repeatable framing scope across phases with tighter tolerances and less labor volatility.

When executed as a true system (not “metal studs on site”), panelized cold-formed steel can support programmatic BTR by enabling:

- Predictable scope: engineered wall panels and repeatable assemblies

- Reduced labor risk: less dependence on scarce framing crews and productivity swings

- Faster framing cycles: panels install quickly when foundations and details are consistent

- Cleaner inspections: consistent assemblies reduce “field interpretation”

- Phase repetition: once the prototype is dialed, later phases get faster and more predictable

This is also where Mainefactured Framing tends to show up in programmatic conversations: precision-engineered, panelized cold-formed steel framing systems delivered nationwide (design/engineering/manufacturing + optional install) with an emphasis on predictable scope, reduced labor risk, faster framing cycles, and repeatability across phases.

When panelized framing is NOT the best fit (credible trade-offs)

Panelization is usually not the top answer when:

- the project is ultra-custom with constant architectural changes

- it’s a small one-off with minimal repetition

- the team won’t lock assemblies early (panelization requires earlier decisions)

- site conditions guarantee constant foundation variance without mitigation

Bottom line: Panelized systems reward discipline. If the prototype won’t stay locked, the compounding benefits won’t show up. If you want the full breakdown, see our panelized cold-formed steel framing explained guide.

10) Next step: Turn this framework into a Phase 1 plan (without re-learning it in Phase 2)

If you’re programmatic (repeat plans, phased starts), the biggest cost swings rarely come from one line item. They come from variance: changing details, inconsistent assemblies, field coordination, and inspection churn that compounds across phases.

The goal of the next step isn’t “a quote.” It’s to lock the prototype and quantify how much cycle-time risk is embedded in your current framing and coordination approach before Phase 1 sets the precedent.

FAQ

1) Which product type is usually lowest cost per unit in BTR?

It depends less on the “type” and more on utilities per door, density, and prototype discipline. Detached can be competitive per SF but often loses on site/utility intensity per door; horizontal apartments can win per door at density; townhomes often win when repetition is protected and rooflines stay simple.

2) Why does detached BTR miss budgets even with “simple houses”?

Because overruns frequently live in sitework and utilities per door, plus inspection and remobilization friction across many dispersed starts—not in the house structure line item.

3) What’s the biggest driver in horizontal apartments?

Execution of assemblies and coordination: life-safety, acoustics, and MEP/structure alignment. When those are standardized early, delivery becomes predictable and repeatable.

4) Are townhomes always the best middle ground?

Only if you control roof complexity and plan exceptions. Townhomes lose their advantage when “small variations” break repetition and create field interpretation.

5) How should operators compare options in underwriting?

Compare all-in cost per delivered door (including site utilities/offsites) and the delivery curve: how many doors per month you can reliably deliver after Phase 1.

6) What levers reduce cost per unit without lowering quality?

Prototype lock, early coordination, simplified rooflines, repeated assemblies, shortened dry-in, stabilized framing productivity, and consistent inspection paths.

7) When does panelized framing help the most in BTR?

When you have repeat plans, phased starts, and labor volatility. That’s when “engineer once, deploy everywhere” becomes a measurable schedule and risk advantage.

8) When is panelized framing not worth it?

Ultra-custom one-offs, very small projects without repetition, or teams unwilling to lock assemblies early typically won’t capture the compounding benefits.

Closing: the decision framework that holds up in 2026

If you’re choosing between townhomes, detached rentals, and horizontal apartments, the winning answer is rarely “the lowest hard cost.” It’s the product type that:

- matches rent and density constraints,

- minimizes site/utility exposure per door,

- delivers a repeatable schedule across phases, and

- reduces labor and inspection volatility through standardization.

In programmatic BTR, repeatability is not a nice-to-have. It’s the lever that makes the pro forma behave.